The Standard of Unconditional Positive Regard

It's one of the hardest things to practice in relationships.

There are ideas that feel simple when you first hear them but difficult when you try to practice them. Unconditional positive regard is one of those ideas.

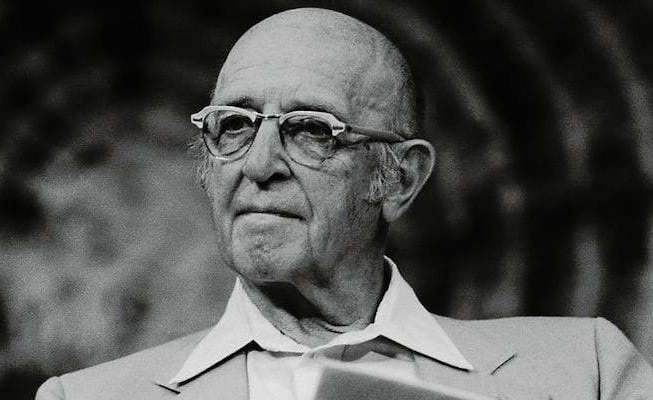

The phrase is most commonly associated with Carl Rogers, an American psychologist who (along with Abraham Maslow) was one of the founders of humanistic psychology, which “focuses on individuals’ capacity to make their own choices, create their own style of life, and actualize themselves in their own way…its emphasis is on the development of human potential.”1

Rogers used unconditional positive regard (UPR) to describe a way of relating to another person that is grounded in acceptance rather than evaluation. In his work, UPR meant valuing and respecting another person without reservation: meeting them where they are, accepting their experiences and stories as real to them, and creating space for exploration without judgment.

In theory, many people support this and may even preach it; in practice, they discover that it’s harder than it sounds. And based on my personal experience with UPR, and dozens of conversations with others, it is quite difficult to put into use.

Most of us move through relationships making quiet assumptions. We draw conclusions quickly. We judge other people. We over-rely on our “gut” and intuition. We interpret other people’s behavior, believe we know their motives, and decide what their behavior or language really means.

Sometimes we do this to protect ourselves. Sometimes we do it because certainty feels more comfortable than curiosity. Sometimes we do it because of jealousy. And sometimes we simply give ourselves more credit than we deserve…and others less credit than they deserve.

Unconditional positive regard interrupts that pattern.

It involves something different: accepting the person as they are, in a positive light, without assuming, judging, or concluding.

This does not mean agreeing. It does not mean trusting someone automatically. It does not require closeness, friendship, or access to our life. Acceptance and proximity are not the same thing. We can accept someone fully while also choosing distance or limiting what we share with them.

And when we find ourselves moving in this direction, we increasingly tap into our human potential…as Rogers and Maslow believed we could.

Acceptance without Agreement

One of the places UPR can be highly appropriate and effective is when someone behaves in a way we dislike or distrust.

If someone lies, exaggerates, or acts in an unbecoming way, unconditional positive regard does not require pretending it didn’t happen. It means accepting that this is where the person is right now. Their behavior may reflect fear, insecurity, or self-protection. They may not even realize they are being dishonest with themselves.

In this scenario, practicing unconditional positive regard helps us move toward acceptance.

Instead of assumption or accusation, we use curiosity. Instead of conclusions, we use clarifying questions. With people we are close to, this may mean asking permission to go deeper rather than confronting immediately. The goal is not to expose or correct or agree, but to understand and accept.

This mirrors how therapists often work. A client might describe loving a partner one week and hating them the next. The therapist does not rush to resolve the contradiction. They continue asking open questions, allowing the person to explore what changed and why. The acceptance creates safety, and safety allows honesty.

Compassion and UPR

Compassion and unconditional positive regard are related but not identical.

Compassion often arises in response to suffering. Unconditional positive regard exists even when suffering isn’t visible. It assumes there is real goodness present, even if it is not immediately apparent. It is less about feeling for someone and more about how we choose to see them.

This perspective changes everyday interactions.

In transactional environments, like buying a car, it may simply mean recognizing the complexity of the other person instead of the simplicity of their role. In social settings, it might mean redirecting an intrusive question rather than reacting defensively. With a partner or close friend, it may mean accepting silence instead of wondering what’s wrong.

Unconditional positive regard allows people to be as they are without requiring them to perform in order to be accepted.

Expectations and Understanding

There is also a relationship between UPR and expectations.

The more expectations we carry into an interaction, the harder it becomes to meet someone where they are. And the more we practice the standard of unconditional positive regard, the fewer expectations we tend to have.

When we have expectations about someone, we believe they will act in a way that aligns with our hopes and desires. As many of us know, that rarely happens, leaving us disappointed, frustrated, annoyed, maybe even angry. We’re not meeting them where they are; we’re expecting them to meet us where we are. Following the standard of UPR, we can lower (or perhaps eliminate) our expectations by focusing on understanding.

When we evaluate, judge, or assume, understanding someone is difficult. We skip past the process of showing curiosity and asking questions because we believe we already know the answers. But when we practice unconditional positive regard and “seek first to understand,”2 we extend grace to the other person.

Turning It Inward

The same practice applies internally with ourselves.

After mistakes, many of us may default to harsh self-talk. Judgments, assumptions, and conclusions appear quickly: “I should have known better. I always do this. How could I be so stupid?”

Unconditional positive regard toward yourself interrupts that spiral. The reminder becomes simple: I’m still good, I’m still learning, I can’t control all the circumstances. The goal is not to avoid responsibility but to remove unnecessary condemnation. It’s an act of self-compassion and self-understanding, enabling you to develop your full potential and leading to higher self-assuredness, self-confidence, and self-regard.

Being on the Receiving End

Speaking of yourself, think about all the times when others judged you, made assumptions about your intentions, or reached conclusions about your life. Reflect back on how many times you felt sadness, frustration, confusion, anger, ire, hopelessness, or isolation because someone didn’t accept you for who you were in that moment.

Whether it was a parent, best friend, spouse or partner, neighbor, or a complete stranger, you were probably dumbfounded. “Where did that come from? How was I so misunderstood? How could they assume that about me? Why didn’t they just ask me?”

One of the most effective ways to learn a difficult relationship practice is to imagine how it might feel if we are on the receiving end of that practice.

Imagine being the recipient of unconditional positive regard. Imagine being accepted for who you are in each moment. Imagine being asked questions and being listened to. Imagine not being judged behind your back, not having your friends and family assume they know what you mean, and not drawing conclusions about your what you say or what you do.

If you can feel in your body what that might feel like, if you find yourself exhaling, or if you notice tears welling up in your eyes, that’s what practicing UPR could do for the people you hold dearest in your life.

Practicing the Standard of UPR

To change relationships, unconditional positive regard must be less of a belief and more of a practice. It shouldn’t have to wait for the big, hard conversations. Instead, it’s most useful in small, non-transactional moments like brief discussions, everyday interactions, and ordinary misunderstandings.

It begins by noticing judgments in real time and pausing before acting on them: creating the space between what you see/hear and what you think/say.

It continues by replacing assumptions or conclusions with curious, open-minded questions.

It concludes by accepting the person based on what you hear from them.

A helpful starting point is carrying a simple thought into your interactions: There is good here, even if I don’t see it yet.

Over time, practicing UPR changes how relationships feel. People become less like problems to solve and more like humans to understand. Conversations deepen. Defensiveness decreases. And the same acceptance that you extend outward becomes available inward as well.

Unconditional positive regard does not mean lowering your standards or ignoring reality. It actually means the opposite: choosing a higher standard of accepting another’s reality. It means choosing to see people as they are and meeting them where they are.

And from that place, you begin fulfilling the promise that Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow envisioned in so many humans: making your own choices and developing your own potential.